“Chaos with Discipline” An Artist’s and Caregiver’s Navigation through VCP Disease

- Cure VCP Disease, Inc.

- Jan 9

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 13

Jon Fasanelli-Cawelti, artist, 1953 - 2021

Diane Calzaretta, spouse and caregiver

In our front room, on an oversized table, lies a small canvas notebook. On its pages are the

artist's printmaking notes for his "Disability Prints” along with reflections of being an artist

living with VCP.

Even with weakening muscles, Jon’s classic cursive flows across the page and he writes, “The disintegration of my body is like an engraving…one cut at a time. A perfect match as long as I keep working! Each is slow.” As an artist, he created an impressive amount of drawings, collages and intaglio prints. Jon was highly trained in intaglio printmaking, a 14th-century printing technique. His specialty was engraving, drypoint and mezzotint. These methods take patience—slow, careful cuts with sharp engraver tools are incised into copper plates, where progress is measured one square inch at a time. These heavy plates, in turn, are inked and manually rolled through a one-ton steel printing press and onto paper, printing one image at a time. Jon considered himself a dinosaur in today’s technology. He continued to write, “Everyone ages; this is just accelerated some. If I need to make deep cuts, I just repeat the cut. Attrition wins out. Do the work as before; constant adjustments are what life is about. I am so lucky! I am learning to do this work with the utmost efficiency from necessity.”

I met Jon in 1978 at the University of Iowa when we were both students. I studied early

childhood special education, while Jon pursued his art degrees. We settled into a 1904 Queen Anne home in Muscatine, Iowa, a town nestled on the Mississippi River where the river runs east to west. It’s there I worked as a teacher and Jon set up his art studio and we started a family. When we decided to have children, there was no indication of Jon’s disease. We didn’t know about his genetic condition. We didn’t know this was the same illness his father and grandmother experienced. We certainly didn’t know there would be a 50% chance of the disease being passed on to offspring. It’s why I so strongly support continued research for VCP and all rare diseases.

Jon’s disease first progressed slowly. 2005, age 51, sporadic muscle weakness. 2009, age 55,

diagnosed with gait abnormalities/motor neuron disease. 2013, age 59, diagnosed with VCP

mutation. 2021, age 67, died at home from complications of ALS-like symptoms. During this

time of adjustments, we purchased an accessible van and made accommodations to our home. A loaned hospital bed from the ALS Association was brought into our first floor next to his drawing studio. Breathing machines and mechanical lifts stood in the dining room for easy access. It took a village, lots of patience and some homemade creativity.

Jon was a practical man. He understood what was happening to him. He also understood that suffering and humor can exist together. He’d always been one to stand by his convictions, and no disease was going to diminish his love for life. There was simply a fresh set of guidelines as he continued to be amused with life, curious and fierce.

Jon didn’t waste a moment. In his final years, he took advantage of a mild winter and got to work creating. “The winter of 2015-16 was mild and nearly ‘open’ since January with little snow - so I started printing a lot.” He knew the longer time went on, the more compromised his body would become.

We learned quickly that facing VCP was a team effort between patient and caregiver. I was

there through all of it—the doctor’s visits, the gradual weakening of his body, and his impactful pieces of art. I was his muse and inspiration. He titled his 2019 art show ATLAS, dedicated to me, his family and friends, and his medical team. I was his Atlas as I held him on my shoulders as we went through this journey together.

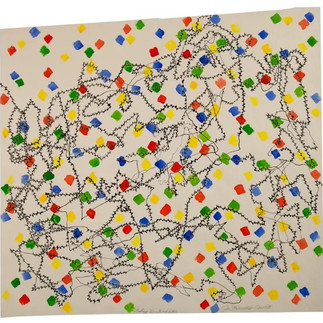

He knew it would be tough but his life was full of paradoxes. He felt immense satisfaction and joy, even with hands that could no longer work the engraving tools. Instead of giving up when printing was over, he transitioned to less physical art forms. He produced over 200 watercolor and pen and ink drawings. “The form is increasingly abstract, organic and intuitive”. Now he looked at art in a new way. His imagery became more abstract, colorful and positive. He felt a freedom to make images any way he wanted. Jon believed VCP gave his art the “opportunity to open up, be braver and use it in a positive way because it’s not going away.” He drew in his studio until the last two weeks of his life.

As we navigated, a new motto emerged: Chaos with Discipline. Even in all the unpredictability, staying true to himself and his goals made life rewarding. VCP is an insidious disease, but Jon didn’t slip into despair. The joy kept much of the depression at bay. “This is the only life we have,” he would say. “And it goes fast.” Instead of fighting against the illness he embraced it and we felt lucky. Since his disease progressed slowly, we had the gift of time.

We loved going to the mountains as a family. While Jon was still able, we packed up the

wheelchair van and drove to 10,000 feet elevation in the snowy mountain range of the Wyoming Medicine Bow Forest. I was nervous to go. There were all these new considerations now, and it didn’t help when the van's brakes started smoking on our way down the steep mountain road. We survived and Jon brought back a copper plate chiseled with a mountain view. Then there was the time his wheelchair got twisted on a carpet at an art museum and the firemen came to assist with detanglement. Or the time he went to visit his mom in a nearby nursing home on a hot summer day and he became immobilized as his electric wheelchair malfunctioned next to the Muscatine Fire Station. Then there was the time his chair became entwined with our living room rug and he sat patiently, meditating, for two hours, until I arrived home from work. No firemen were needed this time as I tugged and pulled with all my strength to release the rug. Needless to say, that was the end of the rugs on the first floor!

Jon taught me to be strong. One month before he passed away he spoke to a group of medical providers at Iowa Healthcare on ALS, Art and Transcendence. When asked how he could be so positive, he said, “he believed there is greatness inside us, take it and turn it into something positive.” And he’s right. We can. But it’s a choice each of us have to make. Jon was an advocate for all people experiencing rare illnesses. He helped healthcare providers, and all of us, see that VCP is something you have, not something you are.

I don’t feel like he’s gone. I’m surrounded by him through his art. He is still in our home.

People who never met him in life can meet him now. His fingerprints are all over the paper, his enthusiasm for life in each splotch of ink. When he was unable to lift the heavy plates, I was his assistant in the print shop. So my fingerprints are all over these works, too.

We all miss him—our girls, our family, and his many friends. He taught me that what is

beautiful isn’t always easy. I came to see the beauty in the difficulty and that the difficult can be beautiful.

Today, I keep his legacy alive by representing his art. I maintain a website, an Instagram page, and curate for local art shows. Through the sale and promotion of his art, others can carry Jon’s spirit forward. If you’d like to view his art and learn more about Jon’s life, please go to jonfasanellicawelti.com or find us on Instagram @jonfasanellicawelti.